We’re overthinking circularity and under-designing it.

Too often, the conversation is dominated by models and what-if scenarios—lifetimes projected, reuse rates assumed, end-of-life outcomes imagined—while real progress stalls.

The problem lies not in the tools themselves, but in how they’re used. The circular economy should be treated as a design obligation, not as a theoretical ambition. Circular design must be a responsibility embedded in the products we create today.

Just as carbon accounting has let companies shift focus from cutting direct Scope 1 emissions to talking about the much larger, harder-to-control Scope 3, circularity risks being diluted in shared, unowned responsibilities. Statements like “It’s recyclable… if infrastructure improves” or “Reuse? That’s up to the user” sound reasonable, but too often serve as cover for inaction.

When everyone is responsible for the system, no one is responsible for the product.

Rather than assessing a product based on what might happen, we should ask:

What is this product designed to contribute to the circular economy?

Is it made for disassembly? Is it repairable, reusable, or recyclable by design? Are its materials compatible with circular flows? Is the information needed to enable this contribution accessible and verifiable?

The Value Hill model offers a useful lens here. It shows that products gain value during design and production, retain it during use, and lose it as they pass through repair, refurbishment, and recycling cycles. Keeping them higher on the hill for longer requires deliberate strategies—not future projections, but design decisions.

This highlights a critical point for businesses: circular design choices are not just sustainability measures, they are long-term value strategies. By designing products that stay in use longer, companies reduce raw material costs, cut waste streams, and strengthen resilience against resource scarcity. The organizations that embed product circularity now will be better prepared for upcoming regulations, stricter reporting requirements, and consumer demand for sustainable products. In short, circularity is no longer optional—it’s a competitive necessity.

This is why circularity should not be treated as a hypothetical impact pathway but as a documented, intentional contribution. Every actor—designer, manufacturer, buyer—should be evaluated not on what might happen downstream, but on whether their product or decision supports circular value creation by design.

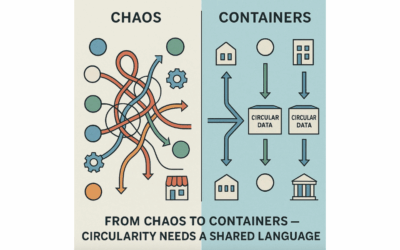

Tools like the Product Circularity Data Sheet (PCDS) make this shift possible. The PCDS avoids speculative assumptions and instead documents verifiable characteristics—modularity, disassembly, material composition, reuse potential—in a structured, comparable, machine-readable format. It provides a common language for assessing how a product is intended to contribute to circularity, regardless of what the future holds.

Complementing the PCDS is the Circularity Tracker, which interprets this data through multiple role-based circularity scores. Instead of reducing circularity to a single rating, it tailors interpretation depending on who is looking: a designer, a buyer, a recycler. This is Circular Data 2.0—data that enables action because it is structured, contextual, and accessible.

More infos: https://circulartracker.eu/

Adopting tools like the PCDS and Circularity Tracker moves circular economy discussions from promises to proof. They provide measurable data on repairability, material flows, and reuse potential—evidence that can be compared across products and industries. This shifts the focus from storytelling to accountability. Instead of claiming “circularity” in vague terms, companies can demonstrate it in verifiable ways. In practice, this enables buyers to make informed choices, designers to avoid hidden trade-offs, and recyclers to work with clear material data. That’s how circular design translates into real-world impact—through transparency, not projections.

This is not to say that scenarios, projections, or systemic models have no place in the circular economy—they do. But their role should be to support strategy, not excuse delay. Without design-level accountability, no scenario will deliver real change.

The circular transition doesn’t need more assumptions—it needs proof, now. The products we design today will define tomorrow’s economy. Let’s make them count.

Let’s stop modelling the perfect future.

Let’s start designing for a better one—one product, one data sheet, one contribution at a time.

Because circularity isn’t a prediction.

It’s a design choice.

More infos: https://circulartracker.eu/

0 Comments